Why We Fight

Eugene Jarecki's latest is an admirable failure of all-too-epic proportions

"Until the latest of our world conflicts, the United States had no armaments industry... [but] we have been compelled to create a permanent armaments industry of vast proportions. Added to this, three and a half million men and women are directly engaged in the defense establishment. We annually spend on military security more than the net income of all United States corporations. This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence-economic, political, even spiritual-is felt in every city, every state house, every office of the Federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society. In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist."

"Until the latest of our world conflicts, the United States had no armaments industry... [but] we have been compelled to create a permanent armaments industry of vast proportions. Added to this, three and a half million men and women are directly engaged in the defense establishment. We annually spend on military security more than the net income of all United States corporations. This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence-economic, political, even spiritual-is felt in every city, every state house, every office of the Federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society. In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist."

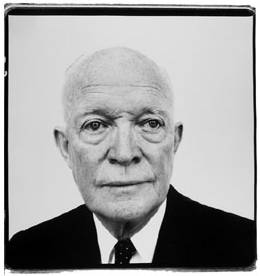

-Eisenhower (Farewell Address, 1961)

Eugene Jarecki's new film, Why We Fight, focuses on Eisenhower's farewell warning about the dangers of a military-industrial complex and paints a convinci ng picture of how that phrase has come to aptly describe the current political situation in America. Jarecki brings a considerable amount of information to the table, but the film fails to pack a cinematic punch and Why We Fight ends up being more like a better-than-average History Channel special than a sophisticated piece of political cinema.

ng picture of how that phrase has come to aptly describe the current political situation in America. Jarecki brings a considerable amount of information to the table, but the film fails to pack a cinematic punch and Why We Fight ends up being more like a better-than-average History Channel special than a sophisticated piece of political cinema.

The primary reason for Why We Fight's cinematic fumbling is that it takes on too much; in addition to "exploring a half-century of American wars" and "the economic, political, and spiritual" forces that drive America to fight, the film also focuses on seven diverse Americans, 16 prominent experts, as well as Eisenhower himself. By taking on so much, Jarecki fails to adequately address the subtler nuances of his topic and the wealth of facts and opinions he employs often provoke more questions than they illuminate.

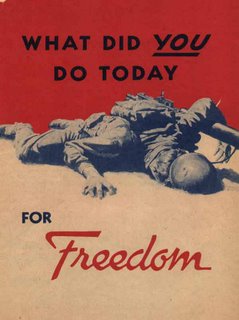

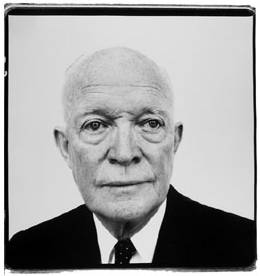

Because of its relationship to The Eisenhower Project, the film was screened at Columbia (Eisenhower was president of Columbia from 1948 to 1953) the night before its American theatrical release. Free tickets were given to the Political Science Department and Jarecki gave a Q&A session following the film. Taking its title from a series of 1944 Frank Capra propaganda films, Why We Fight won the Grand Jury Prize at last year's Sundance and features John McCain, William Kristol, Gore Vidal, Richard Perle, Dan Rather and others. In addition to plentiful footage of bombs, presidents, fat Americans, and unhappy Middle Easterners the film also features the personal stories of seven normal Americans who have played different roles in American militarism.

Because of its relationship to The Eisenhower Project, the film was screened at Columbia (Eisenhower was president of Columbia from 1948 to 1953) the night before its American theatrical release. Free tickets were given to the Political Science Department and Jarecki gave a Q&A session following the film. Taking its title from a series of 1944 Frank Capra propaganda films, Why We Fight won the Grand Jury Prize at last year's Sundance and features John McCain, William Kristol, Gore Vidal, Richard Perle, Dan Rather and others. In addition to plentiful footage of bombs, presidents, fat Americans, and unhappy Middle Easterners the film also features the personal stories of seven normal Americans who have played different roles in American militarism.

Why We Fight could succinctly be described as 'the thinking man's Fahreneheit 9/11"; Jarecki introduced the film by acknowledging that we are all "tired of the shouting match" and offered his film as an attempt to stimulate dialogue. Although Why We Fight was considerably less of a cinematic shout than Michael Moore's contribution on the same subject, it did not, in my opinion, bring much more to the table. Both films used ample historical and contemporary footage, as well as an abundance of facts and "educated opinions"; likewise, both films made similar points, although Janecki's film was much more sophisticated and subtle and a lot less sensationalized and self-righteous.

Why We Fight could succinctly be described as 'the thinking man's Fahreneheit 9/11"; Jarecki introduced the film by acknowledging that we are all "tired of the shouting match" and offered his film as an attempt to stimulate dialogue. Although Why We Fight was considerably less of a cinematic shout than Michael Moore's contribution on the same subject, it did not, in my opinion, bring much more to the table. Both films used ample historical and contemporary footage, as well as an abundance of facts and "educated opinions"; likewise, both films made similar points, although Janecki's film was much more sophisticated and subtle and a lot less sensationalized and self-righteous.

In an interview with the BBC, Jarecki made the following comment comparing Why We Fight to his previous film, The Trials of Henry Kissinger:

"It really followed on from the experience we had making The Trials of Henry Kissinger... I thought I had made a film about US foreign policy but the audiences seemed to be most interested in talking about Henry Kissinger the man. To me, that felt politically impotent because the forces that are driving American foreign policy are so much larger than any one man. With the next film I wanted to go further - I didn't want to stop at an easy villain or a simple scapegoat. I wanted to have a much more holistic approach that really took on the whole system."

Taking on the whole system is a flaw that the overwhelming majority of contemporary "political" movies share. By attempting to tackle an issue as big as "why we fight" in 98 minutes, the film is essentially defanged of all substantial political bite. Although Why We Fight is certainly far more nuanced than a righteous shouting party like Fahrenheit 9/11, it lacks incisiveness of a more moderate (in scope, not politics) film such as Errol Morris's The Fog of War. Why We Fight is like a non-fiction counterpart to films like The Motorcycle Diaries and The Edukators (more on that later), which Richard Porton insightfully criticizes in his article "A Failure of Nerve." Like both films, Why We Fight is full of banal aestheticism (missiles against a striking blue sky, pleasingly-composed panoramas of large weapons) and cliched americana (fat Midwesterners, pick-up trucks, diners, fireworks, etc). Porton describes such films as aesthetically and intellectually impoverished and laments the absence of a "radical narrative political cinema, with no concessions to either liberal pabulum or crude agit-prop" (an absence which he sees as being thrown into startling relief by the recent re-release of Gillo Pontecorvo’s 1965 The Battle of Algiers).

overwhelming majority of contemporary "political" movies share. By attempting to tackle an issue as big as "why we fight" in 98 minutes, the film is essentially defanged of all substantial political bite. Although Why We Fight is certainly far more nuanced than a righteous shouting party like Fahrenheit 9/11, it lacks incisiveness of a more moderate (in scope, not politics) film such as Errol Morris's The Fog of War. Why We Fight is like a non-fiction counterpart to films like The Motorcycle Diaries and The Edukators (more on that later), which Richard Porton insightfully criticizes in his article "A Failure of Nerve." Like both films, Why We Fight is full of banal aestheticism (missiles against a striking blue sky, pleasingly-composed panoramas of large weapons) and cliched americana (fat Midwesterners, pick-up trucks, diners, fireworks, etc). Porton describes such films as aesthetically and intellectually impoverished and laments the absence of a "radical narrative political cinema, with no concessions to either liberal pabulum or crude agit-prop" (an absence which he sees as being thrown into startling relief by the recent re-release of Gillo Pontecorvo’s 1965 The Battle of Algiers).

Although Why We Fight is appreciably more complex than either The Edukators or The Motorcycle Diaries, l ike those films it does more to relieve bourgeois guilt than to stimulate dialogue or deal with Big Questions. Jarecki does indeed tackle the "whole system" -and does it as much justice as can be expected in 98 minutes- but his film is less provocative than one might hope. While he does shed considerable light on the military-industrial complex, his approach turns all criticism outwards: toward the president, the vice president, the arms manufacturers, the congress. Jarecki corrects his former mistake of fixing the weight of America's faults on one individual and instead diffuses criticism into a holistic indictment of The System. However, this indictment is more comforting than one might expect, since Jarecki never takes the step of forcing us to question our role in The System and with whom agency lies. Rather, like Wilton Sekzer, the be

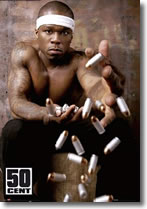

ike those films it does more to relieve bourgeois guilt than to stimulate dialogue or deal with Big Questions. Jarecki does indeed tackle the "whole system" -and does it as much justice as can be expected in 98 minutes- but his film is less provocative than one might hope. While he does shed considerable light on the military-industrial complex, his approach turns all criticism outwards: toward the president, the vice president, the arms manufacturers, the congress. Jarecki corrects his former mistake of fixing the weight of America's faults on one individual and instead diffuses criticism into a holistic indictment of The System. However, this indictment is more comforting than one might expect, since Jarecki never takes the step of forcing us to question our role in The System and with whom agency lies. Rather, like Wilton Sekzer, the be reaved father who requests that his son's name be placed on a bomb headed for Iraq, we can sit back and lament our position as deceived cogs in an imperial machine. 50 Cent's comment in a recent Guardian interview is perhaps a good indicator of the reaction such a film provokes:

reaved father who requests that his son's name be placed on a bomb headed for Iraq, we can sit back and lament our position as deceived cogs in an imperial machine. 50 Cent's comment in a recent Guardian interview is perhaps a good indicator of the reaction such a film provokes:

"Yeah... the war is a business. You have to think about how much money is being made by companies who manufacture weapons... [when asked if this makes him angry] Nah, I just acknowledge it."

Th e success of films like Battle of Algiers and The Fog of War, in my opinion at least, lies in their moderate scope: by focusing on one man (Robert McNamara) or one war (the Algerian revolution), such films are able to bring questions of agency and morality to the fore, rather than leaving them submerged under grand indictments of the status quo. Both films are relatively limited in their subject matter, but both have implications that reach far beyond the time and place their modest running times constrain them to (this was demonstrated by the screening of Battle of Algiers in Pentagon a few months after the invasion of Iraq) . Jarecki is clearly a brilliant man; he is painfully eloquent and exceptionally well-versed in his subject (as he demonstrated in the Q&A), but cinema, at least "political" cinema, is often better suited to allegory than comprehensiveness, and attempting comprehensiveness on a topic as large as "why we fight" is asking for admirable failure at best.

e success of films like Battle of Algiers and The Fog of War, in my opinion at least, lies in their moderate scope: by focusing on one man (Robert McNamara) or one war (the Algerian revolution), such films are able to bring questions of agency and morality to the fore, rather than leaving them submerged under grand indictments of the status quo. Both films are relatively limited in their subject matter, but both have implications that reach far beyond the time and place their modest running times constrain them to (this was demonstrated by the screening of Battle of Algiers in Pentagon a few months after the invasion of Iraq) . Jarecki is clearly a brilliant man; he is painfully eloquent and exceptionally well-versed in his subject (as he demonstrated in the Q&A), but cinema, at least "political" cinema, is often better suited to allegory than comprehensiveness, and attempting comprehensiveness on a topic as large as "why we fight" is asking for admirable failure at best.

(Pictures: Richard Avedon, Eisenhower; General Dwight Eisenhower giving orders to American paratroopers in England, June 6, 1944; Frank Capra film still; Eugene Jarecki; Why We Fight film still; Wilton Sekzer, Why We Fight film still; 50 Cent; WWII poster)

"Until the latest of our world conflicts, the United States had no armaments industry... [but] we have been compelled to create a permanent armaments industry of vast proportions. Added to this, three and a half million men and women are directly engaged in the defense establishment. We annually spend on military security more than the net income of all United States corporations. This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence-economic, political, even spiritual-is felt in every city, every state house, every office of the Federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society. In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist."

"Until the latest of our world conflicts, the United States had no armaments industry... [but] we have been compelled to create a permanent armaments industry of vast proportions. Added to this, three and a half million men and women are directly engaged in the defense establishment. We annually spend on military security more than the net income of all United States corporations. This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence-economic, political, even spiritual-is felt in every city, every state house, every office of the Federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society. In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist."-Eisenhower (Farewell Address, 1961)

Eugene Jarecki's new film, Why We Fight, focuses on Eisenhower's farewell warning about the dangers of a military-industrial complex and paints a convinci

ng picture of how that phrase has come to aptly describe the current political situation in America. Jarecki brings a considerable amount of information to the table, but the film fails to pack a cinematic punch and Why We Fight ends up being more like a better-than-average History Channel special than a sophisticated piece of political cinema.

ng picture of how that phrase has come to aptly describe the current political situation in America. Jarecki brings a considerable amount of information to the table, but the film fails to pack a cinematic punch and Why We Fight ends up being more like a better-than-average History Channel special than a sophisticated piece of political cinema.The primary reason for Why We Fight's cinematic fumbling is that it takes on too much; in addition to "exploring a half-century of American wars" and "the economic, political, and spiritual" forces that drive America to fight, the film also focuses on seven diverse Americans, 16 prominent experts, as well as Eisenhower himself. By taking on so much, Jarecki fails to adequately address the subtler nuances of his topic and the wealth of facts and opinions he employs often provoke more questions than they illuminate.

Because of its relationship to The Eisenhower Project, the film was screened at Columbia (Eisenhower was president of Columbia from 1948 to 1953) the night before its American theatrical release. Free tickets were given to the Political Science Department and Jarecki gave a Q&A session following the film. Taking its title from a series of 1944 Frank Capra propaganda films, Why We Fight won the Grand Jury Prize at last year's Sundance and features John McCain, William Kristol, Gore Vidal, Richard Perle, Dan Rather and others. In addition to plentiful footage of bombs, presidents, fat Americans, and unhappy Middle Easterners the film also features the personal stories of seven normal Americans who have played different roles in American militarism.

Because of its relationship to The Eisenhower Project, the film was screened at Columbia (Eisenhower was president of Columbia from 1948 to 1953) the night before its American theatrical release. Free tickets were given to the Political Science Department and Jarecki gave a Q&A session following the film. Taking its title from a series of 1944 Frank Capra propaganda films, Why We Fight won the Grand Jury Prize at last year's Sundance and features John McCain, William Kristol, Gore Vidal, Richard Perle, Dan Rather and others. In addition to plentiful footage of bombs, presidents, fat Americans, and unhappy Middle Easterners the film also features the personal stories of seven normal Americans who have played different roles in American militarism. Why We Fight could succinctly be described as 'the thinking man's Fahreneheit 9/11"; Jarecki introduced the film by acknowledging that we are all "tired of the shouting match" and offered his film as an attempt to stimulate dialogue. Although Why We Fight was considerably less of a cinematic shout than Michael Moore's contribution on the same subject, it did not, in my opinion, bring much more to the table. Both films used ample historical and contemporary footage, as well as an abundance of facts and "educated opinions"; likewise, both films made similar points, although Janecki's film was much more sophisticated and subtle and a lot less sensationalized and self-righteous.

Why We Fight could succinctly be described as 'the thinking man's Fahreneheit 9/11"; Jarecki introduced the film by acknowledging that we are all "tired of the shouting match" and offered his film as an attempt to stimulate dialogue. Although Why We Fight was considerably less of a cinematic shout than Michael Moore's contribution on the same subject, it did not, in my opinion, bring much more to the table. Both films used ample historical and contemporary footage, as well as an abundance of facts and "educated opinions"; likewise, both films made similar points, although Janecki's film was much more sophisticated and subtle and a lot less sensationalized and self-righteous.In an interview with the BBC, Jarecki made the following comment comparing Why We Fight to his previous film, The Trials of Henry Kissinger:

"It really followed on from the experience we had making The Trials of Henry Kissinger... I thought I had made a film about US foreign policy but the audiences seemed to be most interested in talking about Henry Kissinger the man. To me, that felt politically impotent because the forces that are driving American foreign policy are so much larger than any one man. With the next film I wanted to go further - I didn't want to stop at an easy villain or a simple scapegoat. I wanted to have a much more holistic approach that really took on the whole system."

Taking on the whole system is a flaw that the

overwhelming majority of contemporary "political" movies share. By attempting to tackle an issue as big as "why we fight" in 98 minutes, the film is essentially defanged of all substantial political bite. Although Why We Fight is certainly far more nuanced than a righteous shouting party like Fahrenheit 9/11, it lacks incisiveness of a more moderate (in scope, not politics) film such as Errol Morris's The Fog of War. Why We Fight is like a non-fiction counterpart to films like The Motorcycle Diaries and The Edukators (more on that later), which Richard Porton insightfully criticizes in his article "A Failure of Nerve." Like both films, Why We Fight is full of banal aestheticism (missiles against a striking blue sky, pleasingly-composed panoramas of large weapons) and cliched americana (fat Midwesterners, pick-up trucks, diners, fireworks, etc). Porton describes such films as aesthetically and intellectually impoverished and laments the absence of a "radical narrative political cinema, with no concessions to either liberal pabulum or crude agit-prop" (an absence which he sees as being thrown into startling relief by the recent re-release of Gillo Pontecorvo’s 1965 The Battle of Algiers).

overwhelming majority of contemporary "political" movies share. By attempting to tackle an issue as big as "why we fight" in 98 minutes, the film is essentially defanged of all substantial political bite. Although Why We Fight is certainly far more nuanced than a righteous shouting party like Fahrenheit 9/11, it lacks incisiveness of a more moderate (in scope, not politics) film such as Errol Morris's The Fog of War. Why We Fight is like a non-fiction counterpart to films like The Motorcycle Diaries and The Edukators (more on that later), which Richard Porton insightfully criticizes in his article "A Failure of Nerve." Like both films, Why We Fight is full of banal aestheticism (missiles against a striking blue sky, pleasingly-composed panoramas of large weapons) and cliched americana (fat Midwesterners, pick-up trucks, diners, fireworks, etc). Porton describes such films as aesthetically and intellectually impoverished and laments the absence of a "radical narrative political cinema, with no concessions to either liberal pabulum or crude agit-prop" (an absence which he sees as being thrown into startling relief by the recent re-release of Gillo Pontecorvo’s 1965 The Battle of Algiers).Although Why We Fight is appreciably more complex than either The Edukators or The Motorcycle Diaries, l

ike those films it does more to relieve bourgeois guilt than to stimulate dialogue or deal with Big Questions. Jarecki does indeed tackle the "whole system" -and does it as much justice as can be expected in 98 minutes- but his film is less provocative than one might hope. While he does shed considerable light on the military-industrial complex, his approach turns all criticism outwards: toward the president, the vice president, the arms manufacturers, the congress. Jarecki corrects his former mistake of fixing the weight of America's faults on one individual and instead diffuses criticism into a holistic indictment of The System. However, this indictment is more comforting than one might expect, since Jarecki never takes the step of forcing us to question our role in The System and with whom agency lies. Rather, like Wilton Sekzer, the be

ike those films it does more to relieve bourgeois guilt than to stimulate dialogue or deal with Big Questions. Jarecki does indeed tackle the "whole system" -and does it as much justice as can be expected in 98 minutes- but his film is less provocative than one might hope. While he does shed considerable light on the military-industrial complex, his approach turns all criticism outwards: toward the president, the vice president, the arms manufacturers, the congress. Jarecki corrects his former mistake of fixing the weight of America's faults on one individual and instead diffuses criticism into a holistic indictment of The System. However, this indictment is more comforting than one might expect, since Jarecki never takes the step of forcing us to question our role in The System and with whom agency lies. Rather, like Wilton Sekzer, the be reaved father who requests that his son's name be placed on a bomb headed for Iraq, we can sit back and lament our position as deceived cogs in an imperial machine. 50 Cent's comment in a recent Guardian interview is perhaps a good indicator of the reaction such a film provokes:

reaved father who requests that his son's name be placed on a bomb headed for Iraq, we can sit back and lament our position as deceived cogs in an imperial machine. 50 Cent's comment in a recent Guardian interview is perhaps a good indicator of the reaction such a film provokes:"Yeah... the war is a business. You have to think about how much money is being made by companies who manufacture weapons... [when asked if this makes him angry] Nah, I just acknowledge it."

Th

e success of films like Battle of Algiers and The Fog of War, in my opinion at least, lies in their moderate scope: by focusing on one man (Robert McNamara) or one war (the Algerian revolution), such films are able to bring questions of agency and morality to the fore, rather than leaving them submerged under grand indictments of the status quo. Both films are relatively limited in their subject matter, but both have implications that reach far beyond the time and place their modest running times constrain them to (this was demonstrated by the screening of Battle of Algiers in Pentagon a few months after the invasion of Iraq) . Jarecki is clearly a brilliant man; he is painfully eloquent and exceptionally well-versed in his subject (as he demonstrated in the Q&A), but cinema, at least "political" cinema, is often better suited to allegory than comprehensiveness, and attempting comprehensiveness on a topic as large as "why we fight" is asking for admirable failure at best.

e success of films like Battle of Algiers and The Fog of War, in my opinion at least, lies in their moderate scope: by focusing on one man (Robert McNamara) or one war (the Algerian revolution), such films are able to bring questions of agency and morality to the fore, rather than leaving them submerged under grand indictments of the status quo. Both films are relatively limited in their subject matter, but both have implications that reach far beyond the time and place their modest running times constrain them to (this was demonstrated by the screening of Battle of Algiers in Pentagon a few months after the invasion of Iraq) . Jarecki is clearly a brilliant man; he is painfully eloquent and exceptionally well-versed in his subject (as he demonstrated in the Q&A), but cinema, at least "political" cinema, is often better suited to allegory than comprehensiveness, and attempting comprehensiveness on a topic as large as "why we fight" is asking for admirable failure at best.(Pictures: Richard Avedon, Eisenhower; General Dwight Eisenhower giving orders to American paratroopers in England, June 6, 1944; Frank Capra film still; Eugene Jarecki; Why We Fight film still; Wilton Sekzer, Why We Fight film still; 50 Cent; WWII poster)

6 Comments:

There is so much significance with your use of the 50 Cent quote. Or at least its significance coming from a man like that. The use of rap/hip-hop as a form of social commentary seems to have faded into the background of a massive business industry, and the disconnect between 50 Cent and profiteering of war and violence is disheartening to read. Additionally, the disproporinate number of minorities that have fought for the American cause (I'm thinking of Bob Herbert's op-eds) only further illustrates the huge flaws of America's political ideals and actions.

Yeah, even though the 50 Cent interview is kind of unrelated it is pretty interesting to consider in the context of the movie. Jarecki focused almost exclusively on the economic motivations for war and pretty much ignored some of the more violent aspects of american culture. At the same time, 50 cent's career is kind of like a microcosm of the military-industrial complex in that, at least now, violence seems to be more of a business ploy for him than a necessity of self defense. Whereas, say, 15 years ago, the relationship between violence and hip-hop was perhaps a bit less contrived (although I am admittedly far from the first to point that out and not really qualified to make that judgement in the first place). I don't think, however, that we should hold 50 cent to a higher standard than anyone else (i'm not sure if that's what you meant)- and i think that the "disconnect" you mention is one that most americans (ourselves included) share. Which is basically my problem with the movie: movies that villainize The System are a dime a dozen, and while this is a pretty good one it certainly doesn't break the mold. A good political movie, in my opinion at least, is one that raises quesions about agency, morality, responsibility, collective guilt, or at least something along those lines. And, in my opinion, this movie really didn't do that.

I definitely agree that it's important not to hold 50 Cent to any more standards than anyone else in the hip-hop/rap industry, especially as you have pointed out that his apathetic perspective has its own reasons and if anything, the disconnect was intended as a metaphor and not necessarily finger pointing at 50 Cent. At the same time, I guess my other point was that another question that could be addressed (as opposed to creating some grand narrative of US foreign policy) is not necessarily WHY we fight, but WHO is fighting. We could look all the way back to the US Civil War (or even the Revolutionary War...although in that instance most slaves fought for the British because they promised freedom) and we see that certain minorities have always played a role in our battles and still remain secondary once the dust has settled. Granted, this is a total divergence and I'm sure Jarecki is smart enough to make a documentary on this issue (which is its own category) if he chose to do so, and so I'll conclude that another failure of his film is perhaps that it conflates the mysteries of war in such a way that we ignore fundamental questions about who is actually doing our fighting.

It's funny that you mention that; Jarecki actually mentioned (I forget whether it was in the actual film or in his q&a) that the US pulled out of vietnam when the lottery draft was instituted, extending the draft from minorities and the poor to middle-class white men. But yeah, I agree who is fighting is really an important component to any analysis of why we fight (although "who fights" is not a very catchy title).

But what exactly are you going for here? It sounds like you are trying to deconstruct the "we" in why we fight. Your point, if I am getting it, is that it is not actually WE who are fighting and never really has been. A good point to bring up. Which, in my mind at least, brings up the issue of collective responsibility/guilt and (not to do what you hate) that is basically my point: these are important things to address and Jarecki never really got to them. I guess our points are basically the same?

that comment is pretty "typically american" of me, isn't it?

http://www.newyorker.com/critics/cinema/articles/060123crci_cinema

"But a documentary filmmaker, at the least, must be a journalist seeking to unearth, and not a collagist who assembles miscellaneous footage in order to support what he already believes."

Not bad, friend.

Post a Comment

<< Home