The Soccer War

A revolution every day...

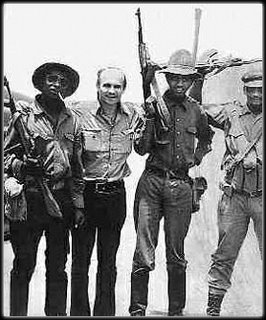

A revolution every day...Although, as a college student, I rarely get to read books for pleasure, I recently finished Ryszard Kapuscinski’s slim (at just over 200 pages) novel The Soccer War. Dubbed by LA Weekly as "the great prose-poet of international disorder,” during his career as a foreign correspondent for the Polish Press Agency, Kapuscinski covered over 27 coups and revolutions, was sentenced to death four times, and was acquainted with Lumumba, Allende, Guevara and numerous other figures of third-world emancipation. From its modest beginning in Accra the year after

I wouldn’t normally spend time talking about a book published nearly three decades ago, but since many of us will soon be leaving our small island for disparate parts of the world, I thought that it might be enlightening to revisit an era crucial in shaping the structure of that world. While we, the under 30s, are familiar with the sexual revolution, Vietnam, and the Civil Rights Movement, the massive global political transformation that occurred during the 1960s is far less present in our collective consciousness. It has been lamented that contemporary journalism on the developing world, and

As a Polish journalist, Kapuscinski’s perspective has little of the latent self-importance or white guilt which might underlie that of a British, French, Belgian, or even American journalist in the same position. As he explains to some Ghanaians in Mpango towards the end of the book, “My country has no colonies, and there was a time when my country was a colony… There were camps, war, executions… That was what we called fascism. It’s the worst kind of colonialism.” Perhaps this background, and the fact that his roots lay behind the iron curtain, gives Kapuscinski’s prose a humility found rarely with other western writers.

As a Polish journalist, Kapuscinski’s perspective has little of the latent self-importance or white guilt which might underlie that of a British, French, Belgian, or even American journalist in the same position. As he explains to some Ghanaians in Mpango towards the end of the book, “My country has no colonies, and there was a time when my country was a colony… There were camps, war, executions… That was what we called fascism. It’s the worst kind of colonialism.” Perhaps this background, and the fact that his roots lay behind the iron curtain, gives Kapuscinski’s prose a humility found rarely with other western writers.

Kapuscinski reminds us frequently throughout his narrative that what he is writing is not a book, but “disjointed fragments;” the plan of an unwritten book fit into the spaces between dispatches and chapters of other non-existent books. Ironically, it is this fragmentation which gives The Soccer War its cohesion; had it dealt with each subject comprehensively it would have quickly grown into a massive unreadable volume; had it focused solely on a few subjects it would have failed to capture the spirit of an era marked global transformation.

The book takes its title from the 1969 war between

Each roadblock he passes demands money and exacts a heavy price upon failure to pay. Along the road Kapuscinski passes burning cars and charred bodies. After two road blocks he has been beaten near unconsciousness, doused with kerosene, and nearly burned alive. Knowing that he has no money left, he decides to run the next roadblock, dodging Molotov cocktails and gunfire in a borrowed Peugeot.

Driving out of

After finishing The Soccer War it is impossible not to wonder what drives someone to put themselves in the near death situations Kapuscinski routinely encounters. Such a person, as one of my friends remarked, “must have a death wish.” While this may certainly be part of the equation, in the subtext of the book Kapuscinski himself offers another explanation. Before he begins the narrative of his death-defying drive out of

After finishing The Soccer War it is impossible not to wonder what drives someone to put themselves in the near death situations Kapuscinski routinely encounters. Such a person, as one of my friends remarked, “must have a death wish.” While this may certainly be part of the equation, in the subtext of the book Kapuscinski himself offers another explanation. Before he begins the narrative of his death-defying drive out of

1 Comments:

Sounds fascinating. This book actually came into conversation with my friend's parents - they're two Indian economists - the other day regarding globalization, so it's a funny coincidence that you wrote this post.

I think, in reference to his quote on Poland's own colonialism, it is really interesting how sometimes the outsider can grasp or portray a situation much better than anyone else. That's what I thought with Kieslowski's role in French cinema, or ... dare I say it, Karl Lagerfeld's role with Chanel (this is strictly a Kathy Horyn quote). But since his book does deal with larger, more global issues, it makes me wonder about what sort of skills or perspectives one needs to really understand the interconnectedness of our global politics. I would agree that perhaps it is something along the lines of his irrevent love of near-death situations...

He almost sounds like a Herzog-Kinski, btw.

Post a Comment

<< Home